Anton Cotteleer

“Memory can change the shape of a room; it can change the color of a car. And memories can be distorted.” (Memento, 2000)

Sometimes, our memories are blurred. You think you remember something; you can picture it very clearly. Until someone comes up with another story that sounds just as credible. Was it like that after all? Did my imagination indeed play tricks on my memory?

Anton Cotteleer is working on a doctorate in the arts. Working from personal and anonymous family photos from the 1970s and 80s, he investigates how haziness - or, to put it more visually, blur - determines our perception of an image and how he might translate this into sculpture, his main discipline.

Photography enjoys a specific status in the appreciation of art. Indeed, viewers tend to think that a picture tells the truth - that it represents a true fact. In the case of Cotteleer's photo albums, this is also largely the case: the images are mostly innocent, personal memories; birthday parties or day trips that he and his loved ones look back on with pleasure. However, as he manipulates the photographs, that innocent, banal factuality disappears. By magnifying the analogue images, he selects fragments, secrets from the darkest corners of the image or actions that, once isolated, take on a more mysterious character.

“When scrutinising the scanned copies, I discover new elements, colours, suggestions and reflections. Since we are dealing with analogue images taken by amateurs, zooming in almost automatically generates an overall ‘blurriness’.” (Anton Cotteleer, An Out-of-Focus Scan, Part 1, 2021)

Due to the blurred nature of the zoomed-in fragment, the object of the photograph is barely recognisable. This creates new forms, new interpretations which Cotteleer subsequently appropriates. In the same way that our memory can sometimes present us with the most irrelevant details, or preserve the vaguest trace of a memory, the artist allows his imagination to interact with the manipulation of a personal and all too familiar snapshot.

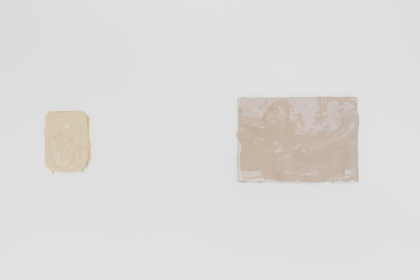

In the first publication issued in connection with his doctoral research, An Out-of-Focus Scan Part I, Cotteleer shows how, by zooming in, cropping and enlarging, he manipulates the photos and infuses them with a new narrative potential. These are the first steps towards the creation of the sculptures that he ultimately wants to achieve. Every stage of the thinking and working process, from the enlarged photos, through the process of sketching, to reliefs in silicone and textile, and finally the realisation of the sculpture, constitutes a new manipulation and reinterpretation of the image. With every anecdote that is told, memories change; with every scan, different aspects of an image come to the fore. Every new intervention on the supposedly factual representation of a moment both questions the veracity of the medium and seeks to create a new artistic narrative.

“Blurredness stimulates the critical distance to familiar phenomena. Only when the blurred photograph becomes too abstract to stimulate the imagination of the observer, the process of active perception is broken off.” (Hilde Van Gelder en Helen Westgeest, Photography Theory in Historical Perspective, 2011)

How does the blurredness - the lack of sharpness - in Cotteleer's photographs translate into sculpture? In earlier sculptures, he used a ''soft skin''. The contours of the sculpture become softer, less sharply delineated, and therefore, in a certain sense, more human. It is precisely this that constitutes the basis of his interest in the blurred, the out-of-focus. Currently, he is also exploring the possibilities of (this) skin in photography and reliefs.

The reliefs that Cotteleer created in the frame of this research form a link between the photographs and the sculptures. The pictures - which, incidentally, can also create their own kind of skin over the years, in the form of mould or other biological or chemical reactions on the paper - usually have a smooth surface, while the reliefs can be made to have just enough texture to produce a seductive tactility.

The process of zooming in on body parts and skin quickly takes on a soft, sensual quality in the photographic images. The artist continues this in the reliefs and undoubtedly also in the sculptures, where fragments of bodies find each other. In a surreal, almost hallucinatory manner, he brings together body parts and objects, which fuse together in a sculptural manner. The question where this path leads to forms the impetus of the exhibition, and the continuation of his research.

Cotteleer recently started working in bronze, after discovering the material’s surprising properties during a workshop in China. There is also a great deal of sensuality in his bronzes: although there are no recognizable limbs, a certain formal, physical movement is enhanced by the shine and reflection of the material. Where in his other sculptures there is some innocence, due to the matte layer of fibers or the lighter colours, in the bronze he explores a more serious and charged plasticity.

Greet Van Autgaerden

“Why else this passion to immortalize the world in its changing faces, why the concern for the most deceptive rendering of every fleeting impression, than to keep the things that threatened to escape within reach of man?”

(Ton Lemaire, Filosofie van het landschap, 1970)*

Landscape is one of the most important art historical genres. From decor to symbolic representation of a feeling, over light-hearted and relaxed to violent and sublime; from panoramic views to flower still lifes: nature is omnipresent in art. Greet Van Autgaerden is not a landscape painter in a traditional interpretation of the word. The landscape is the basis for her works, which follow a long process from perception, over imagination, memory and paint, to the painted image. She mainly finds inspiration in the natural environment of her studio. Trees always play a leading role, with their species-related and individual qualities and branches.

Van Autgaerden's paintings are characterized by a dialogue between figurative – recognizable – landscape elements and abstract forms, often quasi-geometric surfaces in pure, bright colours. Both terms are relative in this case: her rendition of a tree can be figurative in the sense that the specific species is identifiable, but at the same time she works with expressive colors and brushstrokes, making it anything but a realistic representation. However, truthful in the sense that she paints what she sees herself. Through the more abstract elements and areas of colour of this new series, 'human-like' figures creep in for the first time, faceless and with their full energy directed towards the landscape. Here, too, there is no question of a degree of realism; rather, the artist relies on the human tendency to see anthropomorphic features and to be guided by a collective pareidolia.

“So I may cautiously conclude that indeed every landscape contains something of nature as well as something human.” (Ton Lemaire, Filosofie van het landschap, 1970)*

In essence, Van Autgaerden's oeuvre explores perception itself. We, as humans, look at the landscape: what do we see? As an artist she tries to transfer her own perception and insights to the canvas. And within the realization that a ‘real’ image, in principle, does not exist: everyone sees something different, both in the landscape and in the artwork. The highly personal brushstrokes and visual language, in an accessible perspective, enable the viewer to move into the ‘life-size’ painted landscape.

Van Autgaerden derives the title for her series Visions fugitivies from the twenty piano pieces by Sergei Prokofiev. On the one hand, the title is about a flight, away from reality. The natural landscape is a typical escape from our daily, busy existence, from obligations and worries; it is a place that offers time, perspective and space. In a sense, painting is also a necessary escape for the artist; diving into work involves certain difficulties, but may exclude others.

On the other hand, we can also associate the title with the transience of a thought and an image. The human figures that appear in the works enter into a relationship with the landscape to give their thoughts free rein. In nature, a space is created for reflection. That is the case for Van Autgaerden – after all, that's where she gets her unrelenting inspiration – and for most characters who, from Romanticism to the present, figure in the pastoral or sublime landscape. Those thoughts, heavy or light, however, are not the subject of the work. Rather, the landscape and its changeability bear within itself the ephemerality of human reflection. Moreover, there is also an artistic ephemerality: Van Autgaerden perceives an image, wants to preserve it and then reconstruct it in the canvas. Extracting a perceived image – ‘correct’, but rather: true to her personal perception – from the canvas is a constant struggle with paint and form. The image keeps escaping: only in fleeting moments does it show itself, allowing the artist to gradually reveal it further.

Tamara Beheydt