THE CHINAMEN OF OKLAHOMA IN LOVENJOEL

.. who jumped in limousines with the Chinaman of Oklahoma on the impulse of winter midnight streetlight smalltown rain,

who lounged hungry and lonesome through Houston seeking jazz or sex or soup, and followed the brilliant Spaniard to converse about America and Eternity, a hopeless task, and so took ship to Africa, ...

In the first couple of pages of Allen Ginsberg’s poem Howl (1955-’56), line after line starts with the pronoun “who”. It keeps the beat, it is a base to be able to return to and take off from, over and over again. Revolving around this rhythmic axis, Howl, at every turn, tries to cut to the core of the culture and generation Ginsberg is surrounded by.

Mathias Prenen and Haleh Redjaian have chosen Ginsberg’s Chinaman of Oklahoma as the starting point for their collaboration, which “says nothing about who we are, but everything about where we come together”. Not the “who” then, but the “where” as a unifying and in this exhibition often circled factor.

At the invitation of Elly Kog and Bert Verlinden, their work was brought together at the gallery house in Lovenjoel. The white house casts a long shadow over Prenen’s concrete version of a possible Ofra Haza. The exuberant Israeli pop singer, here covered in a traditional string of beads, is alternately singing in Hebrew, Arabic and English to the baroque sculptor and gifted woodcutter around the corner, Grinling Gibbons.

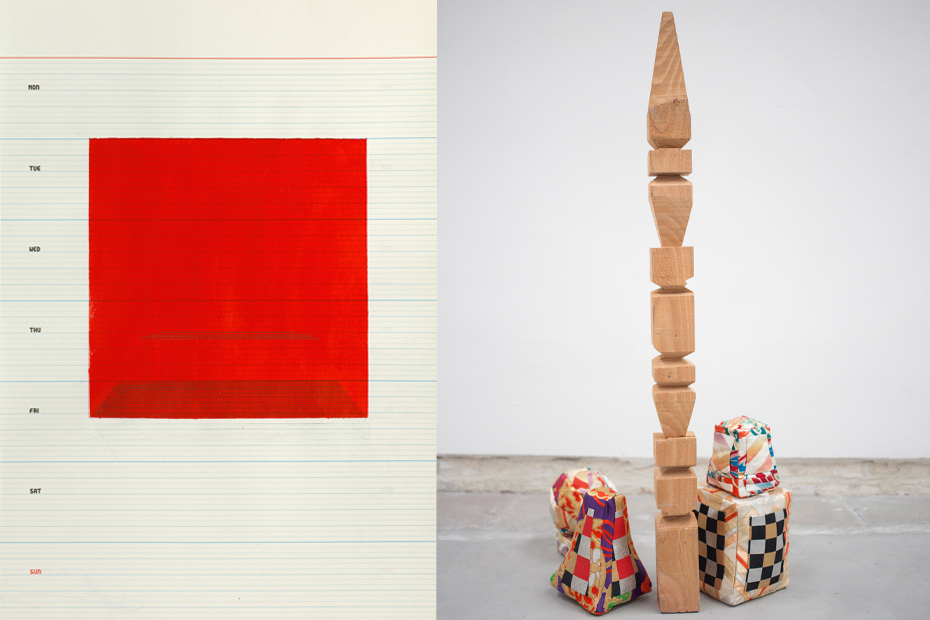

When entering, we are greeted by another #BALUSTER pair by Prenen. The 11th-century Japanese court lady Sei Shōnagon plays off a shiny tallness, refinement and feminity against the rather sturdy and compact Jackie Chan by her side. As a wooden karate machine he is ready to meet any overshadowing movement from her side or from the public. I imagine a situation in which the entrance hall becomes a ballroom and the totems start feeling each other to the fast, poppy beat of New Order’s True Faith (The Morning Sun Extended Remix). This song also refers to the title of a gold-leaf, graphite and acrylic paint collage by Redjaian that opens the space behind the pair. After the dancing, the night makes room for a streak of morning sun appearing on the triangular horizon.

Redjaian’s abstract works take time, ask for a different way of looking. Sometimes they take you from eye level to a parallel space with multiple horizons and perspectives. Drawn on paper or on wood, stretched on tapestries or mounted on the wall, the lines always vibrate differently. Up close, it is clear that it is not the geometric grid, but the human hand that strikes the notes. Shiny shades of gold, rainbows of black or other aquarel colours subtly wave away from the rigid rational systems we use to order or curb the often overwhelming chaos in our lives. Redjaian’s lines repeat themselves endlessly, to a steady cadence, but not always in parallel, sometimes ending in a boldly underlined point or disappearing into a fold. They read like personal scores, settle to the rhythm of a heartbeat or stutter with bated breath.

In both oeuvres, we notice a recurring desire for (de)localization, for trying to find out where something or someone is, or is from. Being in motion, working with repetition and spatialization is what enables them to do this and what coincides in both practices.

Just like the mysterious, unfinished characters in Ginsberg’s Howl, Prenen’s and Redjaian’s work can be read like a mix of cultural, biographical and fictional references, which starts and draws from the same basic vocabulary again and again. They continue to manually draw, sculpt and embroider the same “who” and “where”. In other words, Redjaian’s geometric untitled# grids and Prenen’s #BALUSTER, #FENCE, #ZOME and #KOCHU lexicons keep the beat, just like Ginsberg’s “who”. And although their grids and totems, just like Ginsberg’s Chinaman from Oklahoma, are marked by a certain ethnic or geographic particularity, they are not determined by it.

One work is read against the fore- or background of the other: with a nineteen-year difference, Prenen and Redjaian slide traces of a part of Kempen, Germany, as well as countries like Brazil, Japan and Iran into the room. They connect their own colour, material and technique to modern Western traditions, South-American and Asian ornaments, and they search for their own right combination of all these elements.

By stretching threads in a corner of the house or on a piece of tapestry prepared by a weaver from the Iranian city of Kerman, Redjaian brings the gallery and the original material to life. Prenen adds a fascination with certain historical figures and archetypal ornamental forms. He gives them a new meaning by rearranging and manipulating them, regardless of time and space. Stacked silk pillows suggest a wooden baluster. A concrete baluster becomes a black-painted coat rack becomes an exotic performer. Many balusters together become architecture. A design by the Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer becomes a drawing and then a piece of embroidery. Materials are printed in the shape of a fictional flag design and floor plan of a piece of cotton and shibori cloth dipped in indigo. The scarlet red we know from Chinese antiques accentuates the traces contained in a solid block of wood after it has been manipulated with a chisel, a chainsaw and a sander. Adolf and Karl playfully pull what used to be the leg of a #KOCHU sculpture. Everything is in motion, everything is part of a larger whole.

The column supports the capital, the masculine completes the feminine, the representative the abstract. Concrete is flirting with gold leaf. Steel with cloth. Jackie with Sei. Iran and China overlap. Haleh & Mathias. A thread weaves itself through both oeuvres. It draws lines, between the meaning and its bearer, the tension and its area, the origin and the trace, a system of signs and a free play of forms.

The artists construct their works and exhibition the way writers of the beat generation like Ginsberg set their poetry: there is the meaning of the word itself, but also its rhythmic position in a sentence, and the endless free associating between them. It presents itself as the endlessly varying Chinamen of Oklahoma tuttifrutti game, jumping back and forth.

Liene Aerts, November 2018