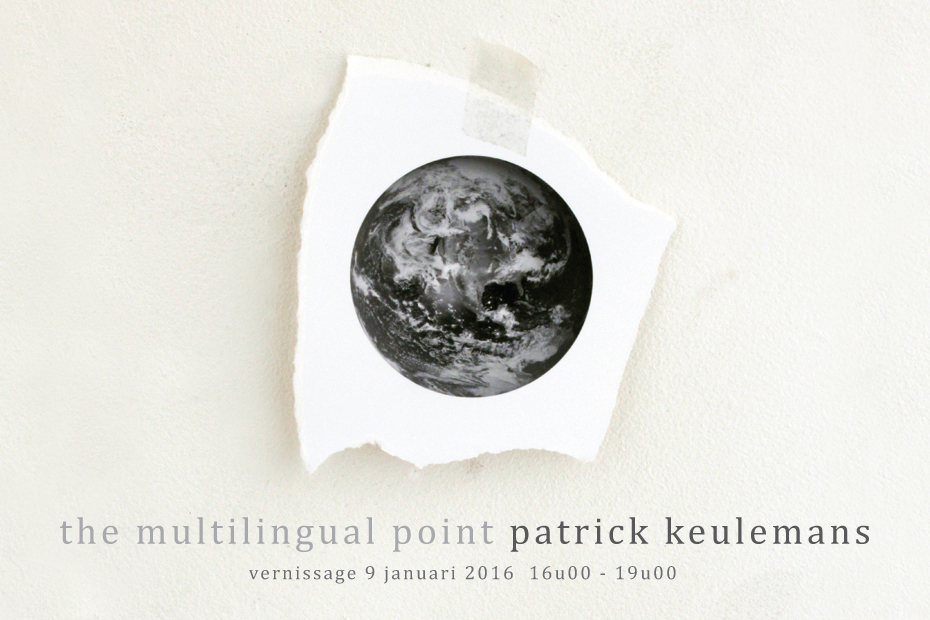

Somewhere in the vast universe, there is a small dot, our earth, ‘the multilingual point’. An assemblage of living and dead languages.

The work of Patrick Keulemans arises from a fascination with language. Language as a vehicle of communication and meaning but which, in its complexity, also gives rise to misunderstanding and the loss of meaning. Within this language, the point is the smallest and most universal symbol. It is a component of letters and characters. It marks the end of every sentence. It creates clarity, delimits, suggests, symbolizes.

In this exhibition, Patrick Keulemans often works with the diverse formal applications and layers of meanings associated with the point. It not only functions as a metaphor for our multilingual world, but also refers to (vestiges of) meaning. Sometimes it is a perforation, then a circle, or simply a point.

In linguistic terms, the primary function of the point is to separate sentences. They are the interrupting signals that increase the readability of a text. In Hermetic – James Joyce, Patrick Keulemans takes a classic piece of world literature – the last chapter of Ulysses – and, via the absence of points and other punctuation, renders it virtually unreadable. He mounts this fragment in a piece of leather, a reference to the first carriers of communication. In a long chain of points filled with letters, but without spaces between words, the linguistic structure completely disappears. The points become a continuous visual pattern. That similar patterns in perforated leather strips might just as easily be filled with bytes of computer language or references to the Israeli issue, raises questions about the interchangeability of symbols, and whether or not linguistic content determines our way of looking at an equivalent object.

The Copy Paste Society is a nod to John Baldessari, Damien Hirst, Roy Lichtenstein, Atsuko Tanaka and Yayoi Kusama, all of whom have turned the point – or sphere – into an identifying mark. The work refers to the question of the copying process. What is an original idea? How do you lend individuality to something as universal and recognizable as a point? Can you claim rights to universal forms and symbols, such as the circle or the point? And if you reproduce them, does it raise questions about copying or plagiarism? Are you a plagiarist if you repeat a trademark, but cast it in a different form? Isn’t language based, above all else, on conventions and repetition, and thus copying? These questions aside, The Copy Paste Society is a work of powerful poetic resonance. Titles of artworks by the aforementioned artists are framed between transparent glass plates and hung in a rhythmic pattern across the wall. The rhythm of the five works adds a further visual layer to the theme of the copy.

The new compact form of Peptalk comprises words and phrases in capsules, like pills to be consumed one by one, but also like the precious vestiges of language and meaning. These remnants can also be seen on two old vinyl records – circles – upon which lost languages are listed.

The tension between past and present is one of the threads running through the exhibition. Sometimes, you can simply feel the history in the beautiful patina that covers the work; at other times, it touches the memory of all that has been lost. On the other hand, the volatility and intractability of contemporary media is never far away, as in Wikileaks Cloud, for example. And despite the critical tone and the air of melancholy, Keulemans regularly succeeds in relativizing himself and eliciting a smile from visitors. With Framework, and its pin points, as a roguish wink.

At first glance, Story of a Tail appears to be a beautifully shaped page of type. Yet there is no visible text. Instead, there is pattern created by plastic tubes that are filled – as alluded to in the title – with horsehair. Small relics with a fascinating content. We see similar patterns in other works, such as 18 pages or DNA, a series of intricately carved, grooved panels that are filled with a sort of Morse code. Visual interpretations of textual representations.

In the attic of the gallery, the tone of the exhibition changes slightly. Conceptual strength and irony give way to a more personalized form of poetry. For the first time, Patrick Keulemans shows a number of self-portraits that were ‘written’, made with a home-made pen: a piece of wood through which the ink flows organically, like the life-giving sap of a tree. Thereby enclosing himself within his own linguistic universe.

Lies Daenen

17. 12. 15