Where did it go?

Stéphanie Baechler

Stéphanie Baechler commutes between Switzerland and Amsterdam but feels equally at home in the European Ceramic Work Centre in Oisterwijk (NL), where she undertook a third residency in 2021. The resulting works form part of this exhibition.

Barely a year ago, Baechler’s artistic practice, which has its roots in the fashion world, unfolded into unique casts in bronze, ceramics or aluminium encased in the traces of textile work. Today, with her cracked ceramics, Baechler is breaking new ground in the medium she calls ‘hardware’. She explores the potential of clay to breaking point – quite literally – and intuitively follows the material’s forms and visual language as well as the actual production process. When the clay reaches its limits, it cracks. In the crevices of these ruptured landscapes, a sparkle of hope can be found here and there. These are tactile surfaces in which one can drown but also be surprised, such as by a sliver of green glaze evoking the magic of new life within the material depths.

The less abstract contemporary bas-reliefs resemble depictions of the vestal virgins due to the presence of frivolous human silhouettes. Tender gestures recall a mother’s touch. When Baechler arranges the contours in an array of soft-toned glazes, resulting in playful spatial collages, the effect is extraordinary. The absence of a loaded and iconographic style makes way for an atypical constructional approach.

Her own embroideries are subtly used to make imprints in the clay, like a ribbon of words that runs throughout her oeuvre. Each work harks back to a previous one and heralds the next. In this way, she continues to build on the material translation of a narrative while also leaving an autobiographical trace, the latter via the titles of the works. Like fragments of thoughts, this exhibition also contains a discourse. Baechler uses one of her own poems to explore an auditory horizon within her practice (in collaboration with sound artist Vica Pacheco).

Those who are familiar with Baechler’s experimental and fragile work know that the carefully constructed packaging boxes have been an inexhaustible source of inspiration for a softer artistic path, one that has evolved in close collaboration with the Textile Museum in Tilburg. In Where did it go? Baechler presents two new Jacquard fabrics or tapestries. The gestures, words and speech balloons can be interpreted as the visual translation of a hunger for a world filled with dialogue and touch. The titles refer to sibyls, the female oracles of the Greco-Roman era. These phophetesses evidently know our future and extend their hands to us. But can we still meet them or do we turn our virtual gaze to the void?

_______

Lieven De Boeck

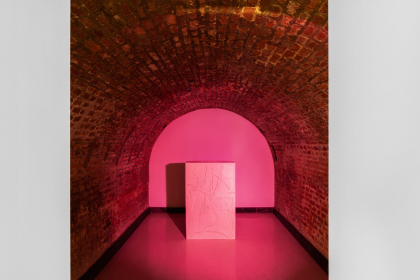

Every exhibition represents a moment in time and an opportunity for art to emerge. In Where did it go? Lieven De Boeck rethinks his own work as a new encounter, an invitation to himself and the viewer to explore meaningful relationships within his oeuvre and in dialogue with the work of Stéphanie Baechler.

Without repeating himself, De Boeck directs and edits his sculptures like a puzzle or a game of Mikado in multiple guises. Where did it go? contains both new and earlier work and is the third iteration of his exhibition Image Not Found, which was previously shown at the FRAC in Marseille (2016) and Objet Trouvé at Museum Dhondt-Dhaenens (2017). As then, the exhibition revolves around the puzzle works that are a formal translation of De Boeck’s self-designed alphabet. Puzzle #2: Demount comprises seven letters, in which E represents the architect Le Corbusier’s anthropomorphic scale of proportions, the ‘Modulor’.

The objectification of the artist’s ideas results in a combination of enigmatic elements that question the status of the actual objects while also playing with the viewer’s sense of comprehension. Nevertheless, De Boeck deliberately opts to present his work on classical plinths. Thanks to their accessible scale, the elements in the works are instantly recognisable. Three-dimensional space is the simplest abstraction of perception needed to describe the dimensions or locations of objects in our everyday surroundings. But closer inspection also makes one wonder about the more fluid dimensions of our observable world. For example, Le Corbusier’s crowning glory resides in the company of immeasurable things such as the melting of ice, the pauses during a chess game or the ripple in a flag. Furthermore, mankind’s radical disruption of nature – which nowadays seems incalculable – is made tangible in the work Ocean Chart, in which you can admire the sparkling plastic floating on the ocean as though studying a rare diamond under a jeweller’s loupe. (This work was previously exhibited in Kasteel de Lovie on the occasion of the Watou arts festival in 2021.)

Although De Boeck enriches the art world with works in such diverse media as glass, paper, textile, neon, fire, water, wind, sand ... the magic of his oeuvre is equally indebted to the absence of matter. From idea to execution, an extensive period of material research precedes the creation of each new work. Whereas Stéphanie Baechler creates fabric, Lieven De Boeck makes new sculptures via a process of reduction, as in the work Letter O. On a sheet of paper from a standard refill pad, Lieven De Boeck, according to the rules of his own alphabet, duplicates a twin figure by lasering away the surface layer, thereby revealing the wood fibres. In the absence of matter and disruption of the pattern, light and transparency emerge. This tension between volume and contour also prevails in the work Five Rings, Found-transported-restored and Hanging, where luminous circles capture and enclose a section of three-dimensional space.

Lieven De Boeck’s practice also describes the fourth dimension: time. His work is often linked to the moment of its exhibition through a metamorphosis or performative action. Again, the action exists through absence, as in the case of the Mikado sticks that represent construction and dismantling but also fragility. In De Boeck’s universe, the viewer is confronted with elements that initially seem difficult to piece together, but is this really the case? Reading dimensions takes time, and time takes space.

February 2022

Louise Goegebeur