Anastasia Bay

An anatomy of movement

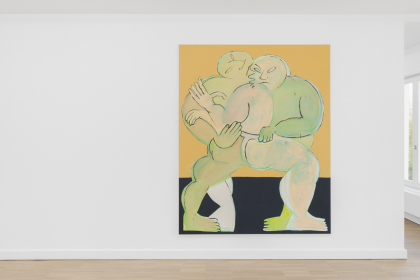

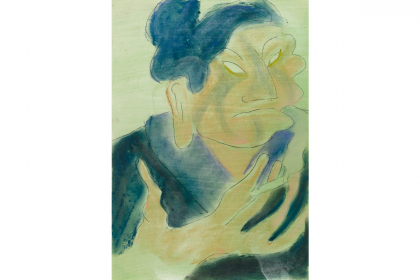

Whether alone or in group compositions, Anastasia Bay’s schematic figures capture the eye. It is not the “disembodied eye” of detached contemplation, but the mind’s eye that joins the cadence of the dancing bodies, the restless divers, boxers and walkers that populate her paintings. A range of different characters fills the canvases with emblematical postures. The boxer, the diver and the fife for example, are recurrent models that keep reappearing, though never fading into sameness. While most characters are closely framed by the canvas, some sneakily cross the line and slip onto the other side. A “floppy leg” connects both parts of a diptych, which pictures a sequence of legs that mingle with each other. The eye moves along as figures start multiplying. Arms and legs overlap in the group arrangements of Bathers, Boxers or Egyptian walk; and bodies seem to exponentially multiply in the layered compositions of works like The Sumos or Sabbath. In addition to intersecting bodies, Anastasia Bay also plays with the figure-ground relationship. The cyclist in Tour de France is eaten up by the blue that surrounds him, and it is the background in Fond Vert that draws out the silhouette of a bather and the stripes of her suit. Figure and ground intertwine with a somewhat disconcerting affinity.

Anastasia Bay draws on a wide range of sources and extracts some of the ‘types’ that run through the history of representation. Among them, we recognize Arlequin wearing his usual chequered costume and a group of dancers who seem to have escaped from Botticelli’s Primavera. The posture of Ingres’ odalisque is remodelled in Reclining woman (Eloïse), which appears at first glance as a close-up of Henri (Le Douanier) Rousseau’s Dream. The attention shifts to Japanese prints in a recent series of paintings that depict chakuhachi players and at the same time hint at the title of Manet’s Le fifre. So the first passage is one of transliteration, in which a set of visual codes is shifted to her own pictorial language. A drawing traced on carbon paper is then copied time and time again until the hand gets used to those lines, until the body has fully memorized those gestures and can apply them onto the surface of the canvas. Thin coats of paint and black pastel give flesh and volume to the bodies, while thicker strokes define the substance of the more opaque backgrounds. The game of transparencies that plays out between the different layers of pastel and paint not only keeps the process visible (including corrections), but also feeds into her rhythmic compositions. As signs of repeated gestures, the lines become traces of movement that open up the paintings to the dimension of time. To use Elisabeth Grosz’s terms, it is a “braided, intertwined” time that Anastasia Bay sets in motion. As Grosz puts it: “There is one and only one time, but there are also numerous times: a duration for each thing or movement, which melds with a global or collective time.” Multiplying layers of visibility, the paintings embody choreographic compositions of lines and colour as a form of bodily inscription that unfolds in time.

The temporal character of the work by no means excludes the artist’s attention to space. The canvas can enclose large-scale bodies, but it can also narrow down its focus to frame specific anatomical features. Eyes can be fierce, crying or ghostly. Anastasia Bay is constantly exploring different ways of treating the relation between the depicted bodies and their material support. She points to the materiality of the canvas when explaining how she applies paint on the back of the painting: “It’s like screen-printing,” she says. As it sinks into the fabric, the watery paint moulds itself into different textures within the painting’s colour field. The artist points to textile work with the intricate patterns of the Samouraï series, but also with all those characters that are oddly wearing nothing but sports socks.

Sofia Dati

Warre Mulder

Witty and imaginative

The ever-expanding sculptural practice of Warre Mulder (b. 1984, Antwerp) is a changing universe full of transformations. Tightrope-walking along the borders between witty and imaginative, truly animated and grinning, spontaneous and orchestrated, the artist brings hybrid sculptures to life: fantastically fabulous creatures, human statues, animals, a plant or an object. They might allude to archetypes, ancestor statues, guards or messengers, and can often be as cheerful as they are disturbing. Spirituality and humour, animism and playfulness, associations and meanings tumble over each other in a personal visual language that has universal appeal.

The artist has been living in a former school in the Dutch polder village of Hengstdijk since 2015. In his studio, he bends a mixture of materials and sculptural traditions to his will. Preferably natural materials such as wood or clay but occasionally homemade mixtures. More often than not, he allows chance to play a role while puzzling together a myriad elements into the creation of a surprising and meaningful work, but he will also combine things according to preconceived ideas and models his sculptures in one piece. He regularly employs motifs and objects that travel through time, whether or not from one culture to another, and which change their meaning along the way. What fascinates him most are primeval human tendencies and how, since the beginning of time, people all over the world have been creating shapes, motifs and symbols in an attempt to grasp reality.

Prehistory, modernism, ethnographic art, folk art, medieval sculptures, comics, science fiction and children’s toys, you name it: cultures and epochs, figuration and abstract patterns all swirl together in a typically colourful art about time and the condition humaine. With a degree in painting under his belt, and partially trained as a sculptor, Warre Mulder focuses mainly on a polychrome sculptural practice of painted works. In the early years, he also attracted attention with his videos. Much later, he used one to pump new life and a different dynamic into his sculpture: a sculptural-pictural video with non-stop motion and a psychedelic aspect.

Spirituality and animism are constantly brought to the fore by exhibition makers. It leads one to believe that a new tendency is emerging in contemporary art. Is there a link between Warre Mulder’s work and animism? “Animism has been present all over the world since the beginning of time. It is one of the primal human tendencies that I look for in my art. Humans have an instinctive and innate urge to see life in inanimate objects. I experienced this intensely as a child and saw my toys as living things. In fact, it forms the basis of my work today. I want my work to acquire vitality, a dose of animism. I want the texture to be able to evoke something tactile, that the materials have a natural origin, that they are handmade. What I am looking for, in all honesty, is a kind of purity. It’s really a search for spirituality and animism. You are looking for it and you want to believe in it, but you can’t quite believe in it and then you begin to put it into perspective.”

What regularly recurs in his art is a play of painted geometric patterns that are reminiscent of folk art or modernist abstractions. “Patterns can even be found on prehistoric artifacts”, notes Warre Mulder. “Apparently, it is a primeval human tendency. It is something that people all over the world did and completely independently, it’s not something passed onwards from culture to culture. There’s a rhythm and a repetition in it, which for me touches on a certain form of life force.

Whether he likes it or not, Warre Mulder’s work is situated within the contemporary debate on globalisation and the plea for multiculturalism. The art world was already clutching at the ideas of the late Édouard Glissant, the Caribbean writer who championed a hybrid society. His philosophy was not far removed from the rhizome model of Deleuze and Guattari. Not that this is what the artist is doing. Cultural mixing is almost self-evident to him: “I feel as if we’re living in an era in which everything from the past and other cultures has simply become part of our own culture and our identity, which is also very confusing. What I make can basically come from anywhere. The changing of certain forms and characters that endlessly recur throughout history and things that travel from one culture to another, it’s a kind of signal that I want to have in my work. I play my modest role in that story by reusing and reformulating such forms and images, without really quoting them.”

His tallest sculpture to date is a ‘Transformer’, albeit one that is afraid of change. The robust figure calls to mind ancestor statues or temple guards from ancient civilisations but, at the same time, it also seems to have escaped from the world of computer games or comics. As an aside: the young Warre Mulder played with ‘Transformer’ figures inspired by the comic book series and cartoons of the same name. Another sculpture recalls Pinocchio. A popular character, including in the world of contemporary art. This is precisely why he has also been utilised by Warre Mulder. The artist also looked at African sculptures of European horsemen and Portuguese equestrian sculptures. Pinocchio is as much an iconic liar as he is an innocent boy. Sitting on a horse that is too small, he reveals his heart. The gesture is a commentary on conquests and our perception of colonialism. In the very same movement, the tradition of the equestrian image is updated.

Christine Vuegen