BIGTHINK

Hung Out to Dry: A Taxonomy of City Blocks by FRANK JACOBS

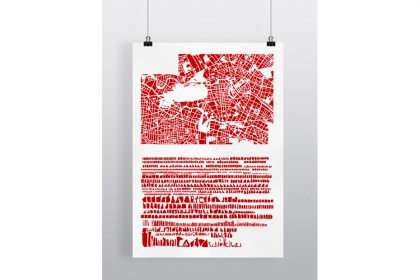

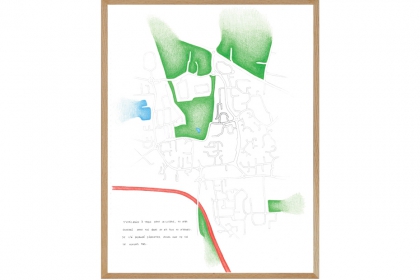

Kublai Khan had noticed that Marco Polo’s cities resembled one another, as if the passage from one to another involved not a journey but a change of elements. In an urbanist twist to the Tales of the Thousand and One Nights, Polo the Venetian regales Khan the Mongolian with glimpses of some fabulous cities in the latter’s huge empire. The stories, collected in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, oscillate between truth and fiction. Each of Polo’s cities displays one unique, defining feature. But they are nothing more than extrapolated miniatures of the homesick Venetian’s hometown. Imagined cities built from the fragments of real ones: something similar is happening in Tout bien rangé, a cartography-based artwork by French artist Armelle Caron. It consists of a series of map pairs, one a blind, but recognisably real city map, the other what looks like an assembly kit for that same city, with its blocks impracticably but neatly arranged by shape and size. The transformational process involved is threefold: the city on map A is deconstructed, its blocks are classified for size and shape, then reassembled in rows, arranged by type, on map B.

The result is reminiscent of butterfly cases and other taxonomical tableaux rather than of a street map. More Linnaeus than Mercator. In what the artist herself calls 'Anagrammes graphiques de plans de villes', Caron strips cities of their spatial context. Roads and rivers become irrelevant, districts and parks disappear. The relationship between built-up areas and empty spaces is obliterated. The city is hung out to dry by its smallest constituent parts. The cartographic compact – maps, however imperfect and partial on paper, are reliable real-world guides – is nullified. The city is un-mapped. Is it therefore also de-coded? The former term implies a loss of information: the city is disassembled, put in storage. The latter suggests a revelation of hidden knowledge: the fragments are pieces of an urban puzzle. For her project, Caron has selected a few world cities: Paris, Berlin, New York, Istanbul. She added a few major French cities – Le Havre and Montpellier – plus the small and new Florida city of Tamarac.

Berlin’s cityscape is reasonably easy to spot thanks to the large Tiergarten park in the upper left quadrant (not to be confused with the rather abrupt cutout in the upper left corner – the map’s legend?). Its city blocks are rearranged as if hanging out to dry, or like rows of saws in a carpenter’s workshop. Istanbul’s curved streets hint at a hilly topography, none of which remains in the stripped version of the map. If this is on the same scale as Berlin’s, this map would indicate that the average Istanbul city block is much smaller, and much more rectangular, than your ordinary Berlin one. Manhattan, the East River, Brooklyn: New York has one of most iconic cityscapes in the world, and is thus easily recognisable. As its real-life grid is already very rectangular, the taxonomy of its city blocks looks very uniform indeed – at least compared to those of ‘organic’, Old World cities. Tamarac is the most eccentric addition. A recent Florida development (built in the 1960s by a car-wash millionaire – turn the name around to get Car-A-Mat), it’s constructed around a regular grid but inside each of those displays the intricate twists and turns of planned suburbia, reflected in a remarkable amount of L-shapes in the abstracted map. Paris is a series of wide, 19th-century boulevards (reputedly wide enough to facilitate the advance of artillery into the frequently rebellious city) imposed upon a medieval spiderweb of streets. The minuteness of that grid is reflected by the intricacy the miniature blocks on the map on the right.

As its name indicates, Le Havre is a harbour town. Extensive docks determine the look of the city’s southern and central areas. The relatively large blocks in the city’s southeast (the industrial area?) break the monotony of the rows upon rows of smaller blocks in the right hand side map. The Montpellier maps must be later works. It just feels like Caron has got the art of displaying a city down to a tee, both the ‘organic’ version (filling out the square of the map quite nicely) and the ‘abstract’ version (a visually pleasing alteration of smaller and larger blocks). Caron’s original exhibition of these works was accompanied by wooden versions of some of the city blocks depicted here, for visitors to rearrange as they saw fit.