Simona Mihaela Stoia (°1982, Hunedoara, RO)

Lives & works in Ottenburg

Video: Jan Weynants

Not everything needs to be painted

Hints of the subconscious in Simona Mihaela Stoia’s works

‘When you see part of a cat’s fur, you don’t need to see its whole body to know that it is a cat.’ This statement was made by Simona Mihaela Stoia during my most recent visit to her studio. Perhaps unintentionally, she gave a description perfectly fitting to her work. Simona’s painting is more about what is not seen, than about what is clearly visually represented.

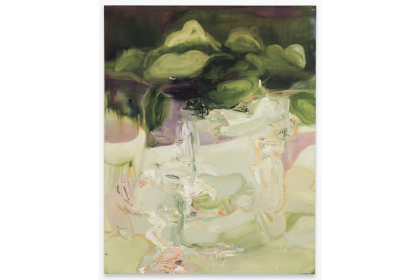

Some might call her work baroque, others might be inclined to see similarities with the abstract expressionism of artists such as Joan Mitchell. What we see is a combination of paint applied in layers and thick masses of paint applied straight from the tube. Parts of the work are almost sculptural. The way Simona speaks about her method resembles the story of a sculptor molding clay: the image appears through a combination of technical, rational gestures of the artist and the matter itself guiding the way. The image appears through adding and also removing matter. The seemingly thinner, negative spaces in the image actually contain many layers of paint, which she removes with a palette knife. Not everything needs to be painted. In contrary, some things may reveal themselves by the act of removing. The image is composed by deconstructing as much constructing.

The overarching theme in Simona’s practice is the loss of, and desire for, a connection between humans and nature (meaning all other living beings, fauna and flora, but also, for example, the seasons). Growing up in a village in Romania, her own connection to the rural environment was strong. She vividly remembers scenes from her grandmother’s work on the land. She remembers growing up ‘surrounded by nature and animals, and on equal terms with them.’

So, it is no surprise that her paintings feature many seemingly organic elements, shapes resembling vegetation and animal bodies. In her most recent body of works, the horizon, the landscape, and most of all the shapes of clouds, play an important part. However, what interests her is an atmosphere, an environment, rather than a figurative scenery. The image never fully reveals itself. As a viewer, we are never sure that what we see isn’t playing a trick on us.

The reason for this, is that Simona doesn’t work with clear representation, but tunes in with her subconscious. How are images formed in our mind? Every moment of every day, we absorb imprints (not only visually, but with all our senses, with our being). Within the mind of an artist, these impressions might trigger new ideas – we might even call them visions (although I have no intention to use this word in a prophet-like manner here). Every painting Simona creates, starts with a (digital) collage of shapes, lent from art history or online archives. The meaning of them hardly matters as, for her, they function only as a reminder of the compositions she wants to activate. The creation of the work itself happens only on the canvas. A good indication of this is her refusal to see the collages in colour: she uses them in black and white, because she remembers colours far better and more vividly than a photograph could ever represent. In contrary, the photograph would trick her, lie. The colours in her memories can only be approached by mixing and applying the paint.

Rather than clear and concrete representations, her creation process is driven by a subconscious urgency, fed by recent or old memories, which are not only in the mind, but also in her senses, in her being. This is where the painting itself takes over. Although undeniably guided by her technical knowledge, her gestures are led to undertake movements or decisions she herself does not fully understand – and, as she frequently states, ‘if she would understand it, she wouldn’t paint it.’

As a consequence, the visceral masses of paint, the interplay between positive (thick, full) and negative (deconstructed, flat) spaces, the uncertain shapes and colours, and the almost hallucinatory distortion between fore- and background, trigger something in the viewer’s psychology, a vague remembrance or an unseen dimension. On that subliminal level, it doesn’t matter whether the bodies we appear to see are human or otherwise: there is a connection, a sense of recognition between beings. In a manner that is rationally inexplicable, the paintings somehow have a living aspect to them, they radiate a sense of life. And because of that, they trigger a certain empathy or even tenderness, touching our existence.

Tamara Beheydt, March 2024