UNREST

The first artistic impressions that Tatjana Gerhard (b. 1974) can recall are her memories of paintings by the Croat Josip Generalić (1936-2004). Gerhard’s Croatian mother knew the artist personally and admired his naive visual language and dreamlike, escapist scenes. She introduced his work to her Swiss family and so young Tatjana grew up in Zurich surrounded by these bizarre, alienating paintings – echoes from her mother’s homeland. As Gerhard remembers it, she was not much in love with the works of Generalić back then; to her they were strange, twisted images of a country she didn’t recognise. But Generalić’s landscapes and peasant portraits are not open-ended, decorative pieces – far from it. To Gerhard, they emanated a mysterious, sometimes ominous power that did not fit at all with her perception of Croatia, a country that she knew primarily from her long, carefree summer holidays spent with her family.

Perhaps the work of Generalić acted like a jamming device during Gerhard’s childhood, affecting the way she perceived her family’s homeland by filtering out certain ideas. However, what happened just a few years later would turn her childhood perceptions on their head for good. 1991 saw Croatia afflicted by catastrophe, Generalić’s fantasy landscape of bare-branched trees entering reality as the backdrop of bloody atrocity, the worst of nightmares made real. With the Yugoslav Wars in the Western Balkans came a sudden explosion of barbarism characterized by horrific violence, death and the bloodbaths of ‘ethnic cleansing’. When the war began, Tatjana Gerhard was 17 years old, on the cusp of adulthood. She experienced the war extremely closely as a result of her contact with a number of family members who had remained in the war zone, and yet also from a great distance, she herself sequestered in safe Switzerland, where she could do nothing but feel a fundamental powerlessness to fathom or respond to such a nightmare.

It’s not surprising that Tatjana Gerhard opted for an artistic education. As an artist, one develops the ability to respond to the world around one, not by raising one’s voice or taking up arms, but by creating images that stimulate thought and imagination. And yet it was only in early 2000, some years after the end of the war in Croatia, that she found a way to articulate her painterly aspirations. Pure beauty or formal experimentation could not bring real satisfaction, nor could the literal presentation of human drama. From the beginning, painting to her was a process of searching without the ambition of pinpoint accuracy. Gerhard’s thoughts will have often drifted back to the naive art of her childhood. Croatia is home to a long tradition of self-taught artists who, despite limited technical knowledge, have been capable of expressing themselves through an extremely personal visual language. Such art will perhaps be considered ugly or kitsch, not in line with contemporary tastes. Nevertheless, it remains anchored in a truly inspired and authentic artistic perspective.

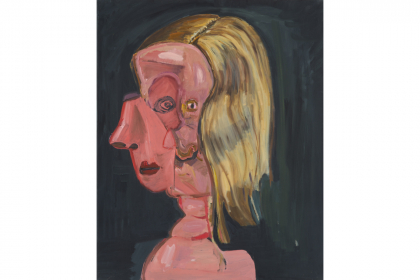

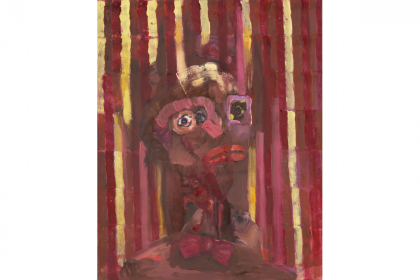

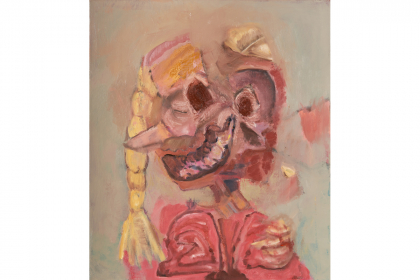

In any event, it was not the intention of Gerhard to make paintings in the tradition of naive art, but rather to seek out a similar, malleable honesty, to herself wield this magic that she had seen flow from certain images. In this sense, her goal was never ultimate beauty. On the contrary, it seems that she seeks precisely to challenge the viewer with ugliness, deformity and grimaces, with wild brushstrokes and ‘dirty’ colour contrasts. Yet none could accuse the artist of deliberately making ugly or bad paintings as a kind of ironic pose; her work is too mature and her attitude too honest and authentic for such aspersions to be cast. What fascinates her is the brutality of ugliness and how she can reshape it to create an exciting, transforming adventure. Ugliness has long been associated with the devilish, and beauty with the divine. Is it even possible to say anything about the human condition without lifting the veil on ugliness? Aren’t the most engaging verses from the Divine Comedy those in which Dante descends to the most terrible depths of hell? Beauty quickly becomes dull and monotonous, while ugliness feeds our imagination. Some exceptionally beautiful paintings were made in 1907, for example, but the work on which the most ink is still spent today is surely that most brutal – and, to some, most horrific – canvas Les Demoiselles d’Avignon by Picasso.

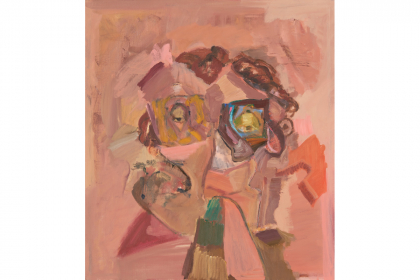

Tatjana Gerhard pursues profusion in her paintings: layer upon layer, image upon image. This excess could well be interpreted as anti-aesthetic, the artist responding to the modern beauty ideal of purification and simplification, to the principle of ‘less is more’. It would seem as if she, in her atelier with her paint and brushes, were embroiled in a battle against the emptiness of the blank canvas. Indeed, her canvasses develop organically and intuitively, the artist not headed toward a preconceived final image. When painting, Gerhard is constantly in search of ways to ramp up the tension in the image. Since for the artist the making of an artwork is a kind of quest, she can’t know beforehand where her painting might lead her, which leaves her vulnerable to becoming lost in a painterly plot in which she must persist until, out of the blue, a solution presents itself. At the same time, the artist herself says that her work is at its most interesting when it’s still in her atelier, balancing tentatively between ‘finished’ and ‘unfinished’. Is a painting ever finished, indeed? Is doubt not an essential element in the development of an oeuvre? And does the artist not extend her painterly quest with every new canvas?

The work of Tatjana Gerhard confronts us with a certain sense of unrest, a feeling that the artist no doubt experiences while at work in her atelier. The art world may seem for many a social and mundane affair, but the life of the artist is often one of loneliness and doubt and the restlessness that results from this. This existential ill-ease that nestles in Gerhard’s work is visually manifest as the alienated person in an undefined space. The world portrayed by Gerhard is hard to accept at first and yet, strangely, very relatable. As a viewer you wander through the sometimes obscure chambers of the artist’s imagination, before finally getting lost and coming out the other side wound up in your own existential questions. Although Gerhard’s paintings may seem forceful, with her images the artist only ‘forces’ our way of viewing to twist and turn back on itself; she doesn’t like to explain herself and most of her works never receive a title. This is a conscious choice as words often give an all-too-clear and one-dimensional meaning to a work, or serve to make the image purely anecdotal. Gerhard succeeds in making images that have immense presence and yet remain ambiguous. This is typical of her searching approach to painting, in which it is just as challenging to gain a grip on the images herself.

Looking at the work of Tatjana Gerhard we are led to cast fundamental doubt on our aesthetic awareness, regarding age-old questions of beauty but even more regarding the state of our Western (image) culture. Throughout the ages, a canon of Western art was slowly amassed by artists, who, holding the monopoly on the creation of images, did their best to make them as exquisite as possible. Today we are inundated with banal, vacuous images – selfies obsessed with ‘the now’, images cut out for quick consumption and equally quick obscurity. Paintings such as those by Tatjana Gerhard are not concerned literally with what is happening now; instead they relate in a contemporary way to our complex visual tradition by playing with the established approaches to colour, brushstrokes and composition. In her work there are allusions to classical genres of art, such as the portrait and the still life, but also to the work of specific painters, such as Picasso, Soutine and Bacon. In addition to this, Gerhard’s work integrates, both consciously and unconsciously, events from her own time and memories from her own life. An inspired painting earns its place in the pantheon of art precisely through the marriage of the contemporary and the timeless. The narratives and interpretations of every painting by Tatjana Gerhard are consciously left open as a challenge to the viewer to seize a grip on our complex and constantly changing world. The image of the state of mankind that is slowly crystallising in her work does then create a sense of restlessness and doubt, but this is precisely how it provokes – on the part of both the artist and the viewer – a process of deliberation that breeds the kind of self-assured decision-making needed to forge ahead in life.