Into The Distance

Caroline Le Méhauté (°1982) questions the relationship between humans and their environment: the earth, but also the cosmos to which that earth belongs. Her sculptures, installations and works on paper are close to nature in the sense that they consist of earthly materials such as peat, coconut fiber and stones. An earth layer thousands of years old or rocks from the indestructible mountains of the Pyrenees; the material, in all its simplicity, already has the power to contain existential questions.

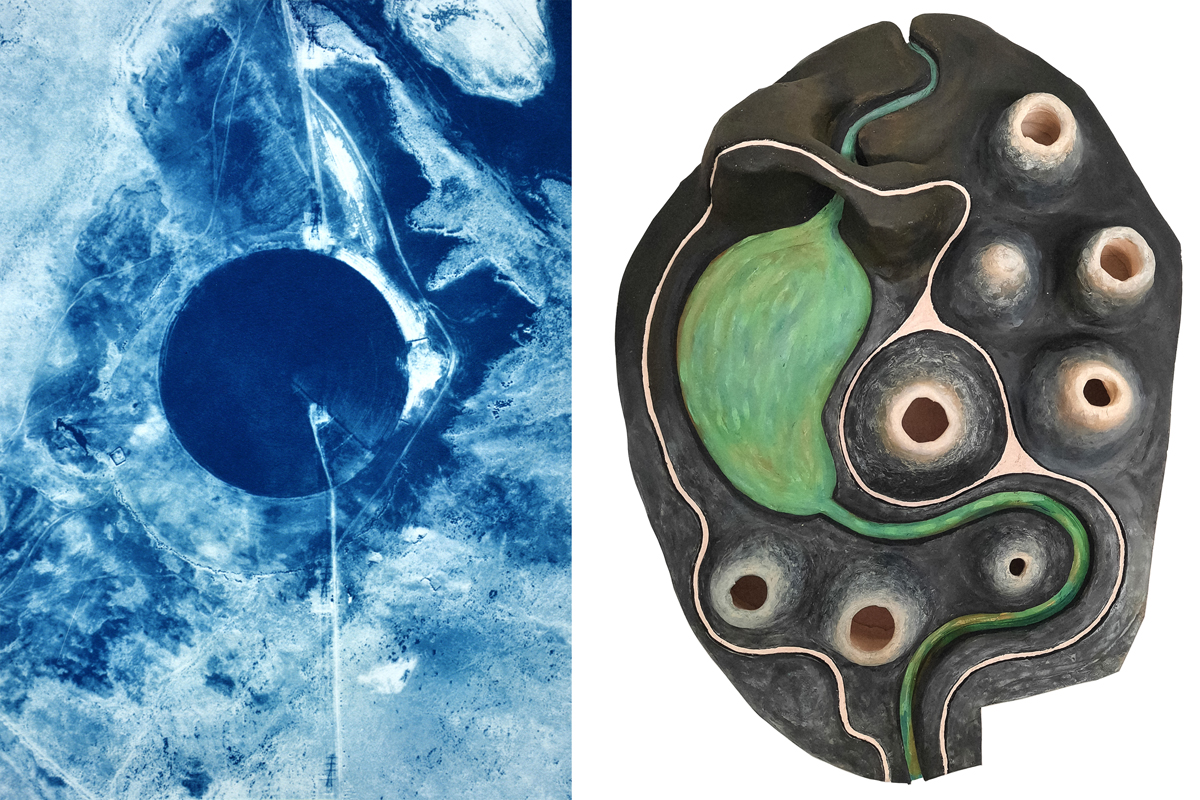

There is an inherent moment of reflection within the abstract stillness of the image. The sight of a – literally and figuratively – elevated surface made of earth, or of a cyanotype (a photographic print made with the direct intervention of sunlight) showing depleted agricultural land from the air, can be enough to put man, the earth, or the cosmos in perspective. Although the history of the strata shown, and the weariness of the nature that surrounds us, are important, the ecological issue is not her primary concern. What really matters to Le Méhauté is a much more fundamental question; an existential, philosophical-poetic reflection on the position of man in his own – natural, much older, richer, larger – environment.

De werken in kokosvezel en andere sculpturen dragen bijna allemaal de titel ‘Negociation’ – onderhandeling. Het gaat de kunstenaar niet om een commerciële onderhandeling of politieke lobby. Wel draait het hier om de continue negotiatie van onze persoonlijke positie ten opzichte van al datgene dat ons omringt. Als mens bevinden we ons in een bepaalde ruimte waar we ons toe verhouden en moeten we op elk moment een balans overleggen met de zwaartekracht. Ook elk ander element, dier, natuurverschijnsel staat in relatie tot elkaar: er is een doorlopende zoektocht naar compromissen binnen de natuur. Op microschaal staat dit besef dichtbij de praktijk van een beeldhouwer, die bij het maken van een sculptuur steeds moet onderhandelen met spelers als het materiaal, de ruimte, de massa, de zwaartekracht.

The coconut fiber works and other sculptures all bear the title "Negociation" – negotiation. The artist is not concerned with a commercial discussion or a political lobby. What matters here is the continuous negotiation of our personal position in relation to everything that surrounds us. As humans, we find ourselves in a certain space to which we relate and we have to consult a balance with gravity at all times. Every other element, animal, or natural phenomenon is also related to each other: there is a continuous search for compromises within nature. On a microscale, this realization is close to the practice of a sculptor, who, when creating a sculpture, must always negotiate with aspects such as the material, space, mass, and gravity.

Van die constante negotiatie maakt Le Méhauté ons bewust door zelf bijzondere compromissen met haar materie, de ruimte en de toeschouwer te sluiten. Haar werk zweeft vaak; op de muur, bijna tegen het plafond, of in een witte achtergrond op papier. Die positionering is niet gratuit: de fysieke perspectiefwijziging brengt ook een mentale confrontatie mee. De aarde komt op gelijke hoogte met de mens; van horizontaal, letterlijk met de voeten getreden en dus nooit van dichtbij gezien, geroken of gevoeld, naar verticaal en face to face. Het hiërarchisch onderscheid valt weg en het besef groeit dat de aarde misschien niet volledig losstaat van de materie waaruit wijzelf zijn opgebouwd.

Le Méhauté makes us aware of this continuous negotiation by making special compromises with her own materials, the space and the spectator. Her work often floats; on the wall, almost reaching the ceiling, or in a white background on paper. This positioning is not gratuitous: the physical change of perspective entails a mental confrontation. The earth is levelled with man; from horizontal, literally trampled underfoot and therefore never seen, smelled or felt up close, to vertical and face to face. The hierarchical distinction disappears and the realization grows that the earth may not be completely separate from the matter from which we ourselves originate.

Earthly nature is a primal force that worked its own way even before the emergence of man. But people often try to control nature. In his artistic practice, Erwan Mahéo (°1968) investigates, among other things, the structures that one creates, with which one shapes landscape and life.

Mahéo works with a multitude of disciplines and materials. He describes his art as a mental space where knowledge is divided into different rooms. His oeuvre is like a mental construction, where each new link can support a previous one, but also revise it. His general interest in the relationships between physical and psychological space often results in installations and objects with architecture as one of the central themes. Paradoxically, he regularly works with textile, a light and flexible material that can nevertheless function as a curtain and spatial structure.

In the last year, his research and works have focused on parks. In the eighteenth century, complex romantic parks were à la mode, teeming with paths, ponds, flowerbeds and pavilions. Some landscape architects went all out and even created hills, ravines and forests. Such gardens or parks not only offer a fascinating walk, but also project a mental trail. The landscape is a translation of psychological wanderings and emotions: a pond brings peace and perspective, a ravine can represent literal and figurative vertigo, and a narrow cave feels claustrophobic.

Mahéo presents a number of ceramic sculptures that evoke models of parks (and represent the future realization a real, life-size park), but also stir up other interesting associations. The colours with which he paints the images, ranging from black to skin-coloured pink, are not very reminiscent of green trees and blue ponds. They do refer, however, to medical drawings and photos; images of the inside of the human body. After all, the park can also be regarded as a complex organism, in which every part is connected and fulfills its own function. There is a certain resemblance between the human organ system and the harmony of paths, lakes and shrubs. In addition, partly due to their vertical, framed positioning against the white gallery wall, the models cause a certain form of pareidolia; the illusion whereby someone thinks they perceive a human face in abstract forms or natural landscapes. The park thus becomes, psychologically and art-historically, a portrait.

Tamara Beheydt