The Quest to Reconcile

Tim Volckaert, The Remedy

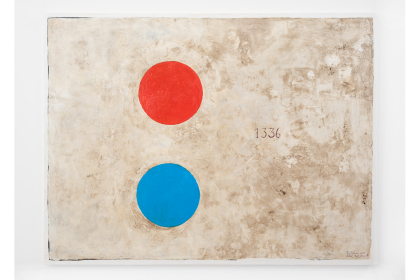

Two entities, one blue, the other red, float in a universe. They can take the shape of a circle, or slightly less random-looking triangular or rectangular structures. Sometimes approaching one another, very occasionally touching, but never giving up their individual character. Just as often they drift apart again in a disoriented landscape. Their dance is more one of distance and ever new attempts at communication, than of pure harmony.

1.

In his new paintings, as in previous series, Tim Volckaert very consciously abandons any hierarchy between foreground and background. Rather than a background, we could speak of an environment. The blue and red shapes float in a skin of sfumato, or in a darkness that nearly threatens to swallow them. A modest gloss is visible on certain specific parts of the canvas, which attracts and absorbs the viewer's gaze. In the exhibition as a whole, each work has its individual, equal appeal.

The dancing geometric shapes are reminiscent of Malevich or Miró, the red and blue colours even bring to mind Mondrian and Vantongerloo. Yet Volckaert's new work is anything but a return to modernist values. The abstraction of modernism tries to free itself from any tension. It is a search for innovation, in most cases through a radical break with all that came before. What Volckaert does is to summarize (and thus abstract) the art-historical baggage he carries as an individual artist. His paintings are neither even nor flat; instead the skin of the canvas bears the scars of previous quests.

2.

In 1336, the Italian poet Francesco Petrarch climbed Mont Ventoux. Today, this would be a completely banal undertaking, a dime a dozen event. Historically, his trip is known as the first tourist excursion. The juncture in time, somewhere between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, is a period of progress, enlightenment and science. Artistically, the mathematical perspective heralds the continuation of Western art history. With science and knowledge, however, also comes disenchantment: everything is given an explanation, perhaps at the expense of wonderment.

In several new paintings, the date 1336, like other words and phrases elsewhere, takes on a formal role. Text gives rise to associations. It is a human element in what is otherwise completely abstract. It attracts us and invites us to dive into the painting: into the material, and into the content. In language, the most common (but always flawed) form of interpersonal communication, Volckaert seeks an additional approach to the viewer. Their gaze is absorbed in an infinite-but-limited, abstract-but-intelligible, open-but-abrasive, attractive-but-exciting universe.

3.

In recent years, Volckaert – whose oeuvre also spans other disciplines, from photography and sculpture to performance and installation – has found a gradual liberation in painting. Extremely aware of the weight and history of the medium, he wrestled with art-historical themes and motifs and made his way to a visual language that enters into dialogue with that tension, in a contemporary manner. It is significant, perhaps even ironic, that he now revisits drawings he made in his early student days, with red and blue circles and rectangles. The date 1336 also figures in them – he was, at that time, already looking for a relationship with the environment and human history. The circle is complete. It is as if his painterly oeuvre imploded, from the present back to the very beginning. The essence turns out to be found in reduction, as well as in liberation. The found abstraction offers an openness to meaning; a potential for a universal narrative.

4.

We live in a polyphonic, but also polarized world. Our Western society is perceptibly experiencing a historic period of transition. Relationships between political, social, economic, ecological and cultural frameworks are under pressure. As individuals we find ourselves in the eye of the storm: what does a personal identity mean in this evolving world, in the grand scheme of things? What goals do we fight for, how do we shape our society? What gives us the right to exist, as individuals and as humanity?

The abstract geometric shapes in Tim Volckaert's new paintings perform a fluid choreography, groping for the most harmonious relationship – which is, of course, doomed to remain constantly in motion. They embark on a quest, a search for authenticity and honest communication; for a relationship to the slumbering sense of an ending; for identity in a changing world and an inescapable, charged and changeable environment; for a new intimacy after an era of isolation, enforced loneliness and quasi-paranoia. Is there a remedy, or are we mired in polemic? Following painful alienation, do we find the path to reconciliation? Artistically, Volckaert has found solutions and freedoms, but that certainly does not mean an end point; rather just the beginning of a newfound pleasure in painting as a connecting act; of a renewed belief in abstraction; of a hopeful (but not naive) essence.

Tamara Beheydt, April 2023