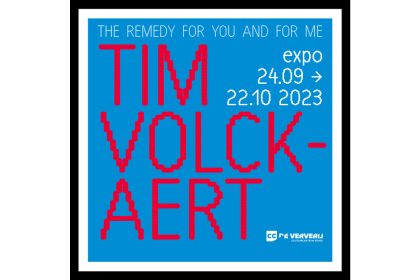

Tim Volckaert (°1979, Kortrijk)

Lives & works in Ronse

Video: © Belfius collection

Throughout his oeuvre, Tim Volckaert (1979) explores a spectrum of disciplines. The relationship between man and landscape runs like a thread through his actions, drawings, sculptures, installations, photography and paintings. How does man relate to his environment? And how is that reflected in art history? In a recent series of paintings, he analysed typical portraits (in the Renaissance and later) in which wealthy citizens allow themselves to be portrayed with a certain self-righteousness, against a landscape setting, which should primarily serve to further display their opulence. He deconstructed and corrected this duality earlier in mysterious paintings, in which foreground and background, and man and landscape merge harmoniously. In his latest works, Volckaert further reflects on how power structures – of man versus the environment, but also of people among themselves – are visible in art history.

In his BBC-series ‘Ways of Seeing’, John Berger describes how female nudes have existed in art history solely for the pleasure of the heterosexual male viewer, who can even own the work. Only very rarely do nudes, gracefully but passively displaying their bodies, look back at the viewer. On the other hand, there is a tradition of portraits of male leaders and prominent figures, brimming with an almost revolting display of power and ostentatious virility.

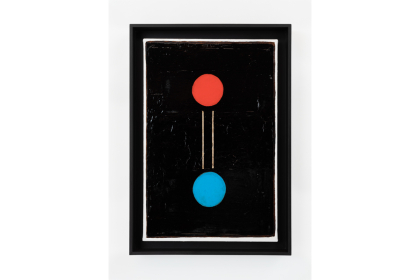

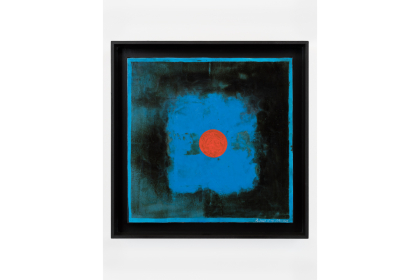

The emergence of such portraits from the Renaissance onwards parallels a growing drive for expansion and the conquest, and consequently subjugation, of the world by wealthy European powers. Many symbolic references to the virility of those portrayed creep into those paintings (intentionally or unconsciously): an obelisk in the background, a rearing horse, an outstretched sword - all relatively clear phallic shapes. A good example is the well-known ‘Bonaparte franchissant le Grand-Saint-Bernard’ by Jacques-Louis David (1801). Napoleon sits on a rearing horse and points upwards: he can conquer heaven, too. In ‘The Back King’ Volckaert isolates this upward movement.

Moreover, in similar ‘official’ portraits, the man’s genitals would often be very pronounced (although covered). Volckaert isolates such bulging, tight pants in ‘Napoleon’, which draws our attention to a bitter truth: (art) history, and by extension the whole world, is accommodatingly attuned to the heterosexual man. In that context he also evokes the theme of a female doll (is it a mannequin or a sex doll?) as the ultimate example of passivity and objectification.

Another, perhaps less obvious, witness of the urge to expand at that time is ‘Scène d'un Naufrage’ (better known as ‘The Raft of the Medusa’) by Théodore Géricault (1818-19). Here too, there is a clear upward movement in the composition. In the way a loose sail is twisted around the mast, Volckaert sees not only a phallic reference, but also an association with so-called "trouser painters": artists who, in the 16th century, were asked to cover the sex of previously painted nudes. He also studies this mast in several paintings as a sign of the ‘phallic’ power relations that lie behind the work and its story.

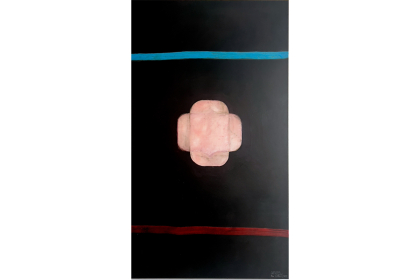

In a new series of paintings, which are not without reason elongated and vertical, Volckaert reveals, among other things, this mechanism in art history. The lack of a background makes the abstract image more pronounced. In ‘Monte Mentum’ and ‘Cutscape (the painting)’ a hint of a romantic landscape looms up like a phallic obelisk, the only shape left out against a black surface. Other works in the series echo the same form, but play with contemporary objects. A liberation can be felt in his letting go of all conventions of foreground, background, and perspective – the skills by which an artist could traditionally demonstrate his mastery.

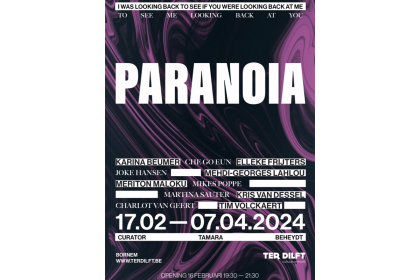

Tamara Beheydt