Nancy Moreno (°1990, Montauban, FR)

Lives & works in Brussels (BE)

Nancy Moreno (1990, FR) lives and works in Brussels. She graduated in 2014 at La Cambre with a Master in Visual Arts (Drawing). Her exhibitions include amongst others: 'Coaltar' at artist-run space Island in 2017 in Brussels (solo); 'Aiming for the Bull's eye' at De La Charge in 2013 in Brussels (solo); 'Noli me tangere' at the Cultural Centre in Namur, curated by Tania Nasielski in 2019 (group); 'La Poursuide des choses évidentes' at the historic building of Brasserie Atlas in Anderlecht in 2019 (group). Nancy Moreno was one of the founders of artist-run space Abilene.

Sometimes, life simply reveals itself to you as an incongruous experience.

(12.07.2018) An unconscious encounter between myself and a painting.

(28.11.2018) A conscious encounter with the artist.

This text spans four months of fragmented observations and thoughts. It is an attempt to capture in words the emerging practice of the artist Nancy Moreno (b. 1990, France).

This summer I fell in love. Isolated on a whitewashed post, it washed over me. In Molenbeek, in the Tower of Babel, I set all language aside. Unwittingly, I stared for countless minutes. The (forgotten) art of looking. I gave myself a pat on the shoulder.

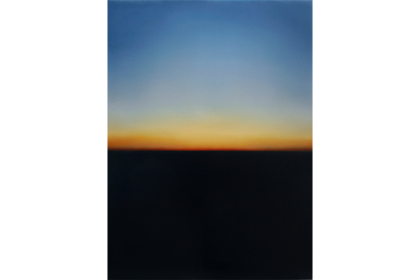

It was made of wood. Not a warped reclaimed panel, or a neatly laser-cut base, but a somewhat thicker rectangle. I suspected that it was plywood. It depicted an abstract nocturnal landscape, in which, thanks to the reflection of the setting sun in the atmosphere, the world was still momentarily illuminated at the point at which the sun had in fact already disappeared behind the horizon. This was no pathetic snapshot, but a transitional image captured in oils, in a way that is only possible in painting.

What’s more, it was the kind of work that causes your gaze to be transformed into a lens. I stepped forward and squeezed shut my eyes into crescent moons so that I could once again take a distance and allow the work some breathing space. I repeated this act a number of times. What I saw was incredibly beautiful. And yes, here beauty is simply not what it seems.

“‘Aube Grise’”, I hear, “It’s by Nancy Moreno”, she adds. Instinctively – like a child of my time – I reach for my phone to consult the internet. In just a few seconds, my visual ‘coup de foudre’ is unmasked by names, facts, dates, and both visual and literary references. It was only later that I realised that this was the moment I had definitively left the vacuum of unwitting observation. Nancy Moreno and I turn out to be just a few months apart in age. She grew up in Montauban, a medium-sized city with historical cachet in the South of France, where painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and sculptor Emile-Antoine Bourdelle were born. In 2014, she graduated with a Master’s in Drawing from La Cambre in Brussels, a city in which she has since been living and working, together with four others who founded the – now dissolved – artist-run space Abilene. I close the tabs because they are gradually supressing my memory of the small painting.

In the months that follow, I pull out the photo that I had taken of the small painting at every opportunity. With an uncertainty akin to that of women in changing rooms, I ask for colleagues’ opinions. This is utterly pointless, because just like women in changing rooms, I had long since made my selection. I carry the image everywhere with me. During the numerous train journeys between Brussels and Hasselt, I project it as an alternative onto the Flemish hinterland, and when I scroll through the pre-programmed wallpapers in my Chinese telephone, I find her mystical gradient – from ochre, via mustard yellow and turquoise, to midnight blue – as a possible option. I decide to contact Nancy Moreno.

She is not available during the day, because she is at work. Moreno has a highly pragmatic vision of the artistic calling, and by extension, of her life. Indeed in her biography, she even writes that after graduating in 2014 she spent three years looking for a job that would provide her with independence and income. A quest that she prioritised over her artistic practice, because during this period she produced almost nothing. After the usual detours into the hospitality sector, she ultimately ended up in the studio of the artist Sanam Kathibi where she found work (which she still does today) as a production assistant. In 2017, the stability of her position in Kathibi’s studio gave her the self-confidence to take up her own practice again.

On a weekday evening in November we finally meet at her studio in Molenbeek, where she shuffles through the austere interior with her Persian cat. Her living space is her workspace, but neither function dominates, in contrast to the many studios that I have visited in the past. She has put all her pictorial works – some seven in total – on display, which means that after a long break I am again standing eye to eye with ‘Aube Grise’; a twilight scene that turned out to be dawn.

The title is based on a passage from ‘Le Solitaire’ [The Hermit], the 1973 novel by the Romanian French playwright Eugène Ionesco in which the main character, a 35-year old man wandering through the modern city, existentially deconstructs his life right down to its sparse foundations. A confronting exercise in introspection, resulting in the usual ‘collateral damage’. The man is a plaything of this emotions and thoughts. He experiences them, but does not understand them, which makes him unable to adjust his behaviour. An eternal failure.

One stimulating passage is the one in which the main character strikes up conversation with a philosopher, who tells him that his existential questions are in essence banal. The main character reacts as follows: Of course,” I answered, “I’m sure you’re aware of these problems; you’ve read a lot, you have a great fount of knowledge. But for me these questions are crucial, they take me and shake me. For you, they’re only cultural. You don’t wake up every morning with fear and trembling, asking yourself what the answers are, then telling yourself there aren’t any. But you know that everyone has asked himself these same questions. And you also know that no one has ever come up with any answers, because there aren’t any. The only difference is that for you the whole thing is files and catalogues… Despair has been domesticated; people have turned it into literature, into works of art. That doesn’t help me.”’

My aim is to unpack this reference in more detail, but suddenly something strikes me that I did not see the last time round. Sitting in the front of the painting, apparently in the belly of the hill, is a rabbit. I see her contours, which thanks to the presence of two long pricked-up ears and a curved back, leave little to chance. I think of a picture from ‘Le Petit Prince’ by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry in which a boa constrictor is digesting an elephant, and the little prince is drawing this act ‘so that the big people can understand. They always need explanations.’ ‘Aube Grise’ is a palimpsest that only slowly unveils its layering.

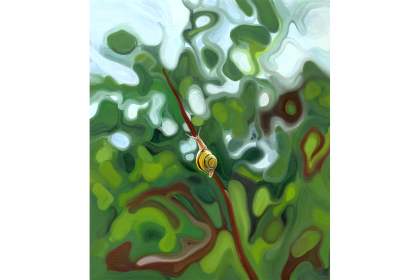

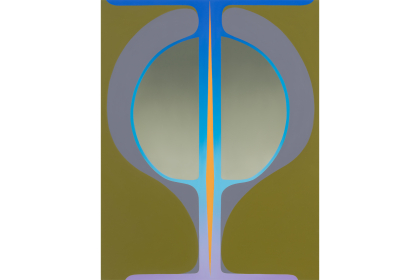

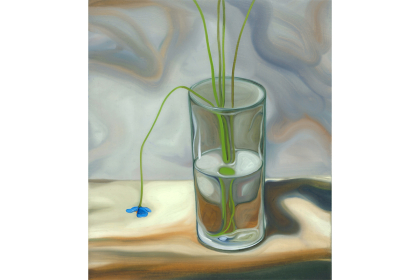

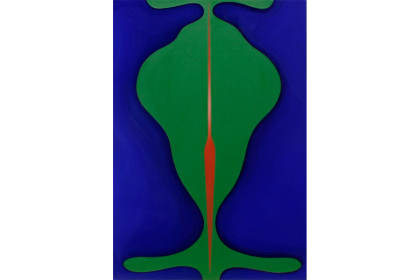

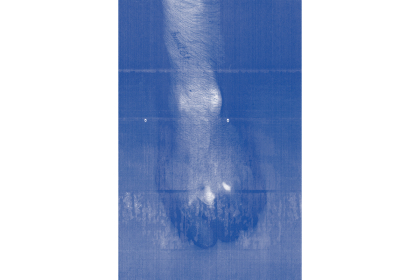

The other works in the studio space are oil on canvas. Large formats that were part of ‘Coaltar’, Nancy’s first and to date only solo exhibition, in spring 2017 at the artist-run space called Island. Stylistically, she is going down a completely different path with these works. The images exist by virtue of colour that she seems to handle like a churning sea of flame so that it conjures up an English garden, a face, or two Calla lilies. Conjuring up seems to me to be a not inappropriate word in this context, because I cannot shake off the feeling that these images possess a mystical, spiritual power.

Nancy tells me that the self-portrait, which in the meantime is unceasingly keeping an eye on me, is her first painting, and that since then she has been repeating this exercise – always with slight variations – a number of times. In the first instance, I interpret the self-portrait as the outcome of a task given to students starting out in every academy and which, as far as I remember, is also sometimes combined with misplaced words of encouragement and platitudes such as ‘everyone is an artist’. However once our discussion is over, I am obliged to adjust my analysis. Just like the writers with whom she likes to surround herself in her thinking, she is on her guard for the dark side of so-called high culture and the intellectuals that concern themselves with it. Her self-portrait is far more than a deformed selfie. It is a contemporary allegory that symbolises human pride. By subordinating herself to this unmasking – with the requisite irony – she demonstrates her complicity, but equally, her sharp self-awareness as a young woman and artist wandering through the modern city.

Louise OSIEKA