Sanne Vaassen (1991, Heerlen) lives and works in Maastricht.

She completed her Bachelor‘s degree at the Maastricht Academy of Fine Arts and Design in 2013 and worked at the Jan van Eyck Academy in 2014/2015. She received the Emerging Artist Grant in 2015 and the Established Artist Grant from the Mondriaan Fund in 2019. She was nominated for the Sybren Hellinga Prize in 2016, the Parkstad Limburg Prize in 2016 and the OPEN Prize in 2020, organised by De Balie and Amsterdam‘s 4 en 5 mei comité. Her work has been exhibited in Maastricht, Eindhoven, Tilburg, Dubai, New York and London, among others.

Please Keep this Secret

As a student at the Maastricht Academy, nature was already an important source of inspiration for Sanne Vaassen (°1991). However, her installations revolve around much more: they tend to ask universal questions. She is fascinated by the unstoppable and continuously flowing transition of her surroundings: not just nature changes constantly (seasons follow each other, plants and trees grow), but our culture too: rules and laws are adapted, traditions and customs gain new meanings, language evolves.

In her work, Vaassen tries to grasp these natural developments, and to questions them. Nature and culture tend to intrude each other continuously. Vaassen discovered a nineteenth century floriographic dictionary, in which flowers are assigned symbolic meanings. During her recent residency at Villa Waldberta (Germany), she gathered all different plants and flowers from the garden, translating them by means of this dictionary. This led to the installation ‘Tussie Mussie’, an archive of dried flowers and plants, whose hidden message is carved in the accompanying filing cabinets.

An inverted kind of translation was also made: Vaassen turned speeches of important political figures into ‘flower language’. Using the flowers and plants appearing in one speech, she created a scent – which, just like politics, is a very present, yet invisible factor in our lives. Which memories do fragrances such as ‘Inauguration by Donald Trump’ and ‘Corona Statement by Angela Merkel’ invoke? Just as the artist wishes to translate more gardens, this series is equally ongoing.

The delicacy of her works, the use of plants, flowers and other fragile materials, could lead the spectator to believe Vaassen’s works are purely poetic. Despite their sensitive force, they are also very critical. By poetical means, the artist questions the world around her. She does this, too, for entrenched traditions, which are barely ever questioned. Every country has its own flag, its own anthem, and its own changing of the guard ritual with an accompanying choreography.

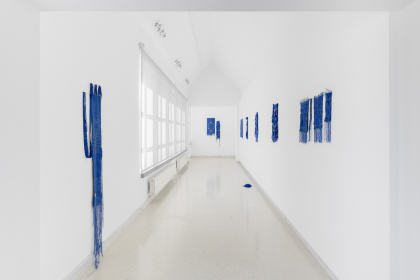

Vaassen analyses and deconstructs such traditions, and questions their symbolism: why do we attach such importance – and why do we feel sentimentally connected – to a piece of cloth? In the ongoing project ‘Flags’, the artist unravels flags, thread by thread. After this time-consuming process, she entrusts this material to a weaver, who interprets it anew. In this new shape, the works can offer new questions: what does a European flag mean, when it is not only literally taken apart, but also metaphorically, now that a country can leave the European Union? How deep can the symbolic trust and the collective unity, which the flag wishes to convey, still go?

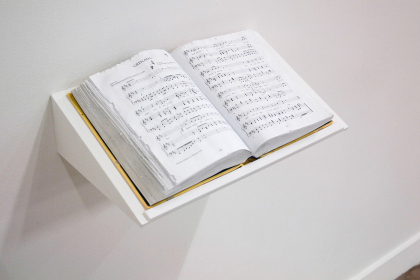

In a similar way, Vaassen surrendered the book ‘National Anthems of the World’ to nature. She mercilessly let snails eat off the paper – again a very patient process, after which the symbolism of the original songs is shook. The scores are no longer clearly readable and the holes giving a view of other notes and words unite the whole into a rather dissonant piece.

The changing of the guards – for example in London – often consists of a complicated choreography, as a practice in handling the weapons the soldiers carry. The dances are powerful, yet sometimes tender. In a collaboration with a glassblower, Vaassen translates these choreographic movements into glass sculptures: abstract and delicate, yet seemingly indestructible.

Vaassen does not force us to reject or adhere certain meanings. She translates existing symbols into new and freer shapes. With them, she asks us, without obligation, to look differently. Why not take another perspective? Why not, occasionally, question that which seems evident?

Tamara Beheydt