Stéphanie Baechler

Care

Stéphanie Baechler (°1983) describes herself as a visual artist who moves between textile and clay. She left the fashion industry to completely devote herself to her own work. The fashion and textile industries are very ephemeral, very fast. Baechler turned things around and started working with clay: an ancient and strong material. In the contrast with the rigidity of the ceramics, textile also found its way back to her practice.

Her practice is similar to an endless weave: one work often seamlessly flows into another. Two large tapestries are inspired by a photographic collage of packing material, which she created especially for another work: a series of whimsical ceramic sculptures. The special shapes create a playful pattern, which also comes into its own through the use of several carefully selected textures.

The use of bronze and aluminium is new for Baechler. She learned how to work with them during a recent residency in Switzerland. While making the tapestries, there were many test weaves – she converts those into wax, bronze with a black patina, or aluminium. The fragments are deconstructions of a whole that was already assembled from loose elements: the several boxes containing ceramic works. The conversion of textile into a more static material is not new to her: in her earlier textile works she was already interested in ‘freezing the movement’: a momentary snapshot of a movement. In a similar way she chooses to treat clay and other materials as threads and, inversely, to ‘freeze’ the treatments of the clay in more traditionally art historical, indestructible materials.

The starting point for this new series of works is an expression of care – the unique and especially created packaging for extremely fragile ceramic sculptures. Baechler has learned to treat her works with exceptional care. The contrast between the softness and protective aspect of textile and the hard, cold (yet malleable) clay, and now bronze and aluminium too – other ‘fire arts’ – forms a thread throughout her practice.

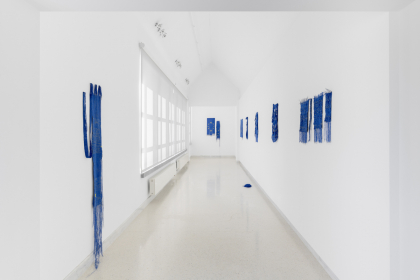

The Fates Are Talking

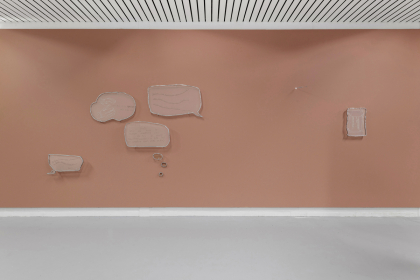

In Whitehouse Gallery’s Project Space, Baechler presents her newly developed work ‘The Fates Are Talking’. “Now you even become the words I was afraid to use,” she says in her letter ‘Dear Line’, published in her first book last summer. The line plays a fundamental role in her practice: as a thread, as a pencil line, as a basic shape for the clay when it comes out of the extruder, and now also in the form of language. The fact that text appears in her work is hardly surprising: ‘text’ and ‘textile’ both descend from the Latin word ‘texere’, which means ‘weaving’.

The three Fates, in Greek mythology, determine people’s destinies: Clotho spins the thread of destiny, Lachesis measures it, and Atropos cuts it when our time has come. With these three ancient characters, Baechler creates a contemporary dialogue, embroidered onto a see-through fabric piece of five meters long. The conversation revolves around current concerns, such as the climate and our dependency on technology. It also involves some personal stories and memories of the artist.

Baechler was also inspired by Seth Siegelaub (1941-2013), an American gallerist, curator & researcher who collected textile works. He wrote about the narrow link between textile and social history, and about how textile was one of the industries standing at the cradle of capitalism. The giant piece was created with a embroidery machine that normally operates at high speeds with 168 needles. The artist decided to use only one needle, giving the work a much more individual, patient touch. The font of the text was especially designed. With this method, and with the content of the text, she focuses on the process. At the end of the dialogue, Atropos transforms into Care and asks for “more modesty, humility, honesty and humanity!” With all this, Baechler counteracts the current customs of a textile industry that is increasingly focusing on large and fast production.

Sanne Vaassen

Please Keep this Secret

As a student at the Maastricht Academy, nature was already an important source of inspiration for Sanne Vaassen (°1991). However, her installations revolve around much more: they tend to ask universal questions. She is fascinated by the unstoppable and continuously flowing transition of her surroundings: not just nature changes constantly (seasons follow each other, plants and trees grow), but our culture too: rules and laws are adapted, traditions and customs gain new meanings, language evolves.

In her work, Vaassen tries to grasp these natural developments, and to questions them. Nature and culture tend to intrude each other continuously. Vaassen discovered a nineteenth century floriographic dictionary, in which flowers are assigned symbolic meanings. During her recent residency at Villa Waldberta (Germany), she gathered all different plants and flowers from the garden, translating them by means of this dictionary. This led to the installation ‘Tussie Mussie’, an archive of dried flowers and plants, whose hidden message is carved in the accompanying filing cabinets.

An inverted kind of translation was also made: Vaassen turned speeches of important political figures into ‘flower language’. Using the flowers and plants appearing in one speech, she created a scent – which, just like politics, is a very present, yet invisible factor in our lives. Which memories do fragrances such as ‘Inauguration by Donald Trump’ and ‘Corona Statement by Angela Merkel’ invoke? Just as the artist wishes to translate more gardens, this series is equally ongoing.

The delicacy of her works, the use of plants, flowers and other fragile materials, could lead the spectator to believe Vaassen’s works are purely poetic. Despite their sensitive force, they are also very critical. By poetical means, the artist questions the world around her. She does this, too, for entrenched traditions, which are barely ever questioned. Every country has its own flag, its own anthem, and its own changing of the guard ritual with an accompanying choreography.

Vaassen analyses and deconstructs such traditions, and questions their symbolism: why do we attach such importance – and why do we feel sentimentally connected – to a piece of cloth? In the ongoing project ‘Flags’, the artist unravels flags, thread by thread. After this time-consuming process, she entrusts this material to a weaver, who interprets it anew. In this new shape, the works can offer new questions: what does a European flag mean, when it is not only literally taken apart, but also metaphorically, now that a country can leave the European Union? How deep can the symbolic trust and the collective unity, which the flag wishes to convey, still go?

In a similar way, Vaassen surrendered the book ‘National Anthems of the World’ to nature. She mercilessly let snails eat off the paper – again a very patient process, after which the symbolism of the original songs is shook. The scores are no longer clearly readable and the holes giving a view of other notes and words unite the whole into a rather dissonant piece.

The changing of the guards – for example in London – often consists of a complicated choreography, as a practice in handling the weapons the soldiers carry. The dances are powerful, yet sometimes tender. In a collaboration with a glassblower, Vaassen translates these choreographic movements into glass sculptures: abstract and delicate, yet seemingly indestructible.

Vaassen does not force us to reject or adhere certain meanings. She translates existing symbols into new and freer shapes. With them, she asks us, without obligation, to look differently. Why not take another perspective? Why not, occasionally, question that which seems evident?

Tamara Beheydt