To (be)hold color

Witold Vandenbroeck & Marie Zolamian - Whitehouse Gallery

By Ilse Roosens

“This was a shock: it never dawned on me that an art historian might have beheld color, but never held color. (...) The corporeality of color was simply primary; something to handle, pour, slosh around, feel, drip, smudge, tape off, and experience.”

Sillman A. (2022). On Color. In C. Houette, F. Lancien-Guilberteau & B. Thorel (Eds.), ‘Amy Sillman Faux Pas. Selected Writings and Drawings,’ pp. 51-77. Parijs: After 8 Books.

In ‘On Color’ (2022), painter and author Amy Sillman describes how she often fails to distinguish between color and paint. Pigment and material are interchangeable for painters; they seem to be one and the same. In German, therefore, ‘Farbe’ encompasses both meanings. It is this versatility of the word ‘Farbe’ that is the starting point for Marie Zolamian and Witold Vandenbroeck. Color and paint are the building blocks of their work, bounded or spurred on by time. Both are painters who can talk endlessly about the material: how it feels, smells, its history and what does or does not work for how they envision their paintings. Their practices and interests may be miles apart, but in their passion for paint they find each other.

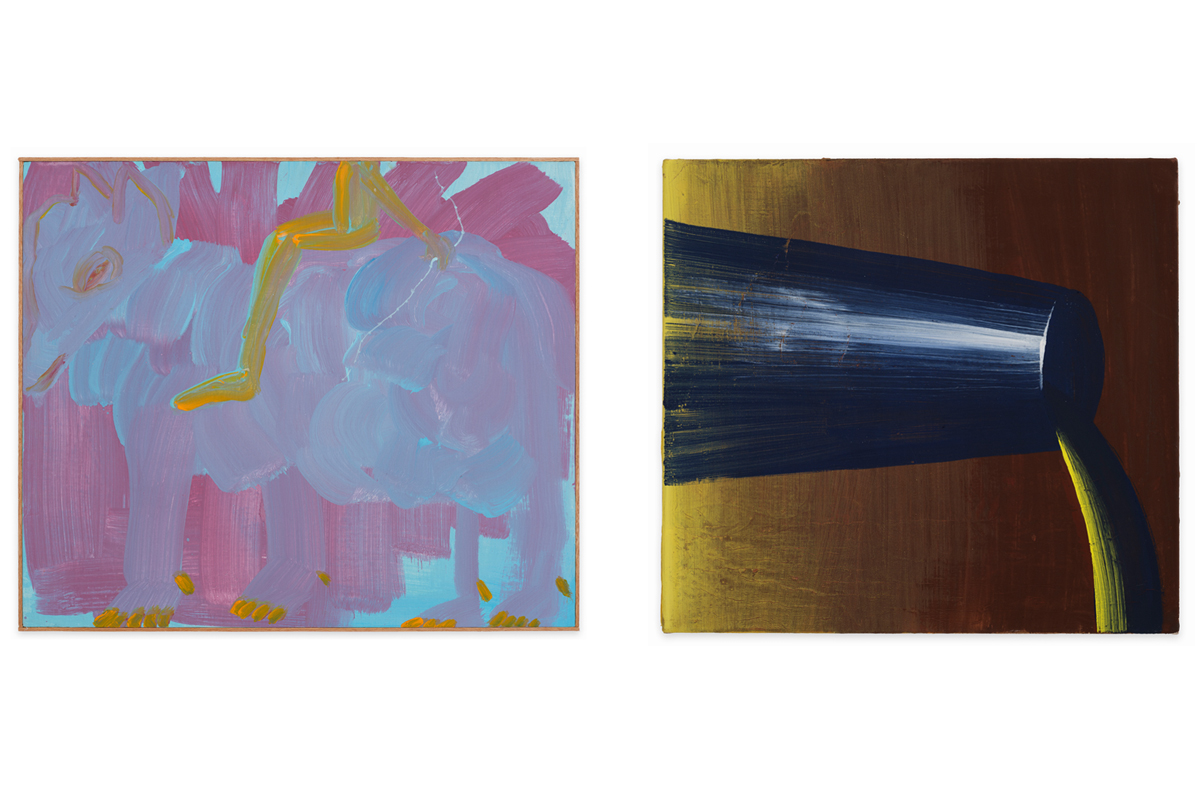

The colors and brushstrokes they want to put down determine their choice of materials. Glue size, a traditional material known primarily through the old masters, is something they both find inimitable. Zolamian prepares her canvases with it, Vandenbroeck mixes it with pigment, so it becomes Distemper. The oil paint that Zolamian then uses for her wet-on-wet technique has a long drying time. By employing it very precisely, this method allows her to explore the possibilities of transparency. Sometimes she works with several layers that she lets dry and then covers up, creating depth, but most of the time she leaves out perspective and shadows. The forms are then stacked on top of each other and become alive with color accents, gradations and semi-translucent segments. The forms - usually plants, animals or figures between humans and animals - arise associatively and are more a prompt for the application of surfaces than fragments from a preconceived narrative. It is only at a later point that the meaning of the figures unfolds to her and helps her better understand her surroundings and the world. For her, painting is like a journey she undertakes where both recognizable things and new events present themselves, where successful and unsuccessful experiences occur through chance and experimentation, after which she can approach the world that surrounds her in a different way.

---

Creating a kind of parallel world with paint and brush helps Zolamian find her own position in reality. Vandenbroeck's canvases are his personal interpretation of that same reality by capturing it in clenched, smooth objects that reflect or absorb light. He connects these recognizable round sheaths to the way we as humans move through the world. We slip through them and, as individuals, barely manage to leave a trace. We are surrounded by a structure that determines our route, similar to the flow of water through rivers, of blood through our veins, of electricity through cables, of streetcars through tunnels. He paints the tubes, pipes and chalices with distemper, a material that needs to be warmed up so it requires a quick and focused way of working. Indeed, Vandenbroeck seeks a moment of clenched energy to paint an entire canvas without overworking it. The pigments create full colors, they are opaque and heavy to the touch, so that even when rendering transparency and movement, they radiate stillness and tranquility above all.

So not only the shapes and figures are important to Zolamian and Vandenbroeck, but at least as central are the colors and the way the paint is applied. They choose very precisely their pigments, binders and carriers for the right result, but also for the way they want to paint.The pace, texture and format influence their choice of materials and tell something about their individual approach.Their materials even give structure to the year: Zolamian prepares her canvases in April and Vandenbroeck reorients his method each season according to the temperature.

When beholding a painting, all these aspects are usually pushed into the background. What remains is an image analyzed in terms of content and formalism. But concepts can also be derived from the materials and the application of layers of glue and pigment to the canvas. As Josef Albers described it in his color theory, theory arises only as a conclusion after practice.

To understand theory properly, it is crucial to know the practice of the artist, and that includes the speed or slowness of painting, the smells and textures of pigments and glue, the heat or cold of the studio, the weight of the paint, the sensation of the support and the application of the layers of paint. All these aspects make color a material, an object, from which infinite forms can flow.